Restoring Claude Monet’s ‘Water Lilies’ at the Portland Art Museum

Despite her lab’s clinical setting, the Portland Art Museum’s conservator, Charlotte Ameringer, works primarily by eye.

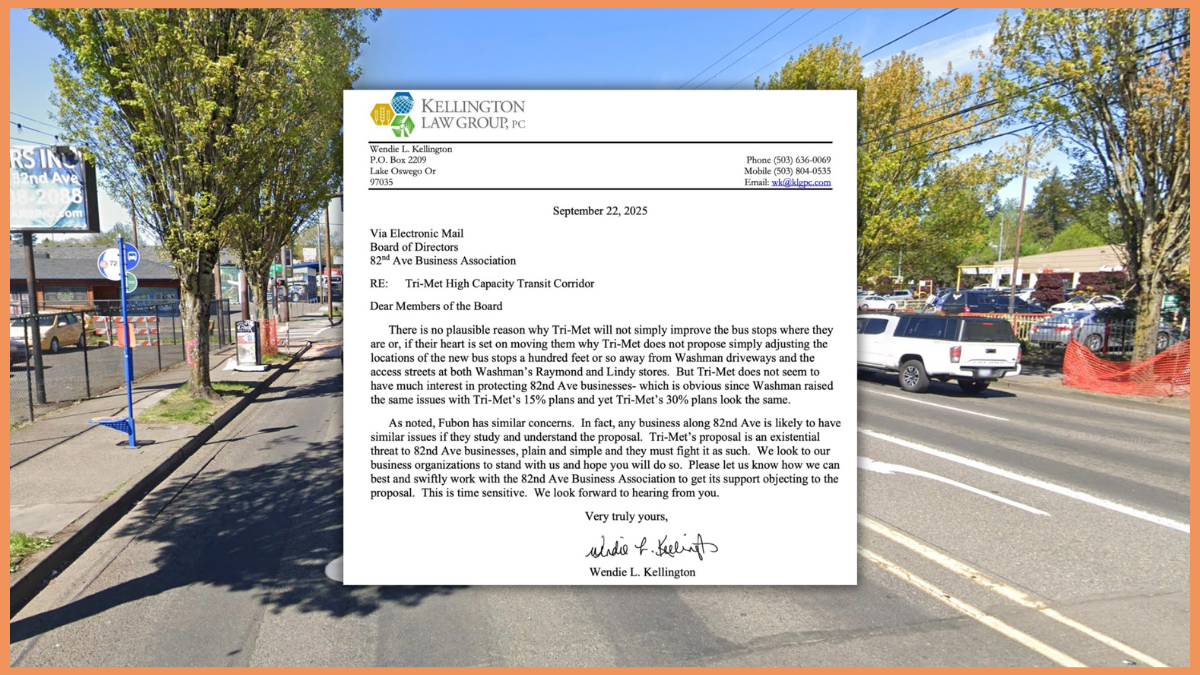

The five-by-six-foot painting, stripped of its frame, sits on a complicated easel: a patient in this sterile conservator’s lab. The conservator, Charlotte Ameringer, is touching Claude Monet’s Water Lilies (1914–15). She just traced the Impressionist’s energetic brushstrokes with a bare pointer finger; now she’s grazing the holes that once held brass pins.

“I call it ‘communing with the painting,’” she tells me. She spent a month inspecting it, reading everything she could find about the piece. Her job involves both deciding what should happen to the painting and carrying out the physical work. When the Portland Art Museum bought it in 1959, she says, the canvas was slicked with a protective varnish, lined with a second sheet of canvas, and stapled taut: safe, but obscured by its prophylactics.

When Ameringer started at the museum a few years ago, its prized Monet caught her attention, and not in a good way. The “rather thick varnish coat,” she says, gives it a wet shine that oversaturates its colors—far past Monet’s delicate pastel tones. (Dealers commonly varnished paintings at the time, despite artists’ objections.) She’s currently using a solvent, a cotton swab, and a surprisingly vigorous rubbing motion to remove this “egregious” varnish, a months-long process. From there, it’s a dance of tweaks and touch-ups balancing surgical rigor, historical scholarship, and more than a little artistic instinct. Though the painting has scarcely come off view in the past 65 years, construction closures as the museum expands its campus gave Ameringer her window. With help from a Bank of America Art Conservation Project grant, she’s giving a behind-the-scenes look at the process through a video series and installation.

The videos keep the painting on view, Ameringer says, but this peek into her lab also provides an approachable entry point. Beeping motion sensors, tweedy historians, and sheer fame drive a wedge between art and viewer, especially art of this stature. A major artist’s most celebrated series easily becomes a concept divorced from reality: It’s almost impossible to imagine a Monet as something you could actually touch.

Part of that’s to do with his towering legacy. “It is possible to think of Monet as providing the one certain and complete criterion of Impressionism,” the art historian William Gaunt once wrote. Impressionism was named, pejoratively, after one of Monet’s paintings, but unlike his contemporaries he stuck with its ideas. He depicted, as the eye sees, the light refracted by his subjects rather than the material objects themselves. His meditations on London’s houses of Parliament, haystacks, the Rouen Cathedral, the Seine, and finally his pond at Giverny were never repetitive, because in each he caught the mood of the day, of the hour. Of course, Monet didn’t invent being sensitive to light, but his ideas of how to treat it were revolutionary.

Ameringer spent months removing the painting’s unwanted, glossy varnish inch by inch.

Monet painted his beloved water garden about 250 times from the 1890s until he died in 1926. But 1914 was a particularly pivotal year. Mourning the recent deaths of both his second wife and oldest son, Monet, in his mid-70s, set out on his opus: eight panels that hang as two panoramic tableaux at Paris’s Musée de l’Orangerie. Spanning 328 linear feet, it’s been called the “Sistine Chapel of Impressionism.” PAM’s painting is also dated to 1914.

“I think our painting really is at the forefront,” Ameringer says. “And I think it’s telling that he kept it.” Monet never sold the painting that ended up in Portland, evidenced by its posthumously stamped signature, and his surviving son, Michel Monet, kept it for most of his life; PAM is the only other owner. There is a lot of magic at work here, much of it owing to a self-mythology Monet seemed happy to help construct, Ameringer says, “always in these three-piece, tweed suits with the pocket square.” Sorting reality from legend feels somewhat beside the point. But Ameringer’s job is to forensically investigate how he constructed his paintings so she can recreate and preserve his moves.

At a glance, her lab is sober. Lights are 4,500 Kelvin, close to daylight, and the walls are a clinically neutral “photo gray.” An entire field, “technical art history,” is devoted to studying artists’ materials and methods; however, conservation is a largely intuitive practice. Costume? Apron. Gloves? They’d get in the way. When touching things up after removing the varnish, “inpainting” cracks or damaged areas, Ameringer works entirely by eye: brush, palette, and pigment.

This is why she spends as much time studying Monet’s mind as she does the chemical composition of his pigments, hoping, a century after his death, to tap into the Frenchman’s spirit. The looseness is jarring considering the painting is worth roughly eight figures. But it also seems necessary. Watching her work, really work on the painting, collapses some of its stature, the frightful aura of scholarship that hovers over it in its precious, institutional context. Watching her bare hands touch the painting turns it back into a painting.

Share this content:

Post Comment