Portland’s First All-Ages Venue in Over a Decade

On the second night of 2025, a line of young Portlanders wrapped around Holocene, the converted warehouse club on SE Morrison, their bodies pressed determinedly toward the door. Inside, underground artists with names like the Red Strings, Lil Jerzy, Sheyana, and Ant Kash geared up backstage to play Icebreaker, the annual music festival the venue has hosted since 2018. Though they looked the part and drew a crowd, playing a club like this is rare for these acts. More often you’ll find them gigging in the Park Blocks or at an art gallery between exhibitions. Because despite their talent, ingenuity, and professional training, these musicians, sound engineers, producers, and stagehands are barred from almost every venue in the city. Why? They haven’t turned 21 yet.

In the ’90s and aughts, Portland had a fair number of venues open to minors, like X-Ray Café, La Luna, and a later-era version of Satyricon. But the scene dropped off. As industry profit margins tightened, most concert halls offset costs with alcohol sales, opening a liquor-law can of worms that makes hosting underage performers and audiences exceedingly tricky. Which is likely why the city hasn’t seen an officially sanctioned, devoted all-ages venue since Backspace closed in 2013.

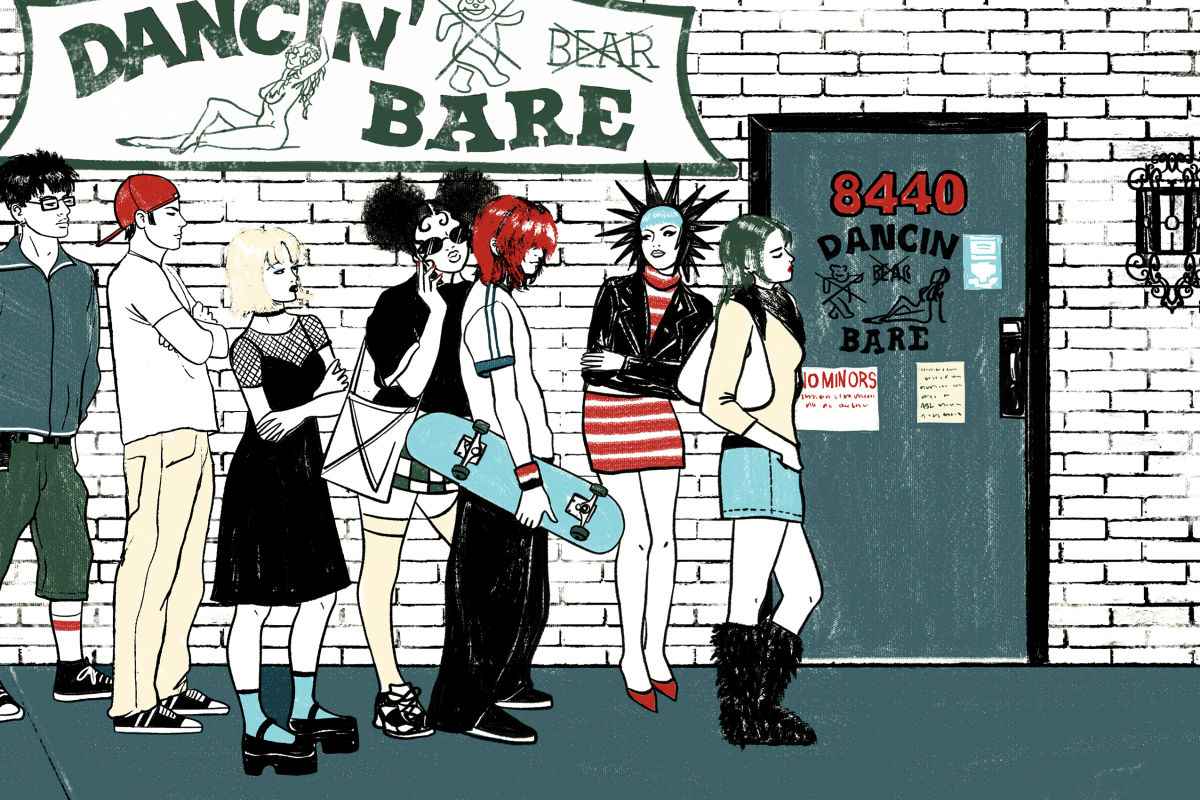

That’s about to change. Those kids who take over Holocene for one day each year are part of Friends of Noise, a local nonprofit devoted to rebuilding the city’s underage scene. They’ll finally have a home base in the Off Beat, an alcohol-free, all-ages venue that’s—more than a little ironically—housed in the former Kenton strip club Dancin’ Bare.

André Middleton, executive director of Friends of Noise, practically lived at places like X-Ray Café amid Portland’s grunge-era heyday. But it wasn’t until 2016, when his then-13-year-old daughter started asking to go to concerts, that he felt the gap left by those old venues. “I couldn’t take my young person to go see live music in a small venue the way I had,” he says.

At the time, Middleton worked for Portland’s Regional Arts and Culture Council (RACC), where part of his job was getting more local musicians to apply for grants. When he was approached by a coalition from the local scene who were looking to revitalize the city’s all-ages options, he was eager to help. Today, Friends of Noise is a one-stop shop for young musicians. Geared to support people of color and of queer identities, the nonprofit hosts free workshops covering every corner of the business: how to set up a PA, stage fright vs. stage presence, independent finance 101. It also helps teens test their skills with hands-on, paid gigs, putting on concerts across the city, running a weekly XRAY.fm show, and hiring out its alumni for local events. There is still an age requirement: No one over 25 can work a Friends of Noise show.

The nonprofit counts 200 teens and 20-somethings on its roster, including buzzy rapper Bird Bennett and the sprawling seven-piece R&B group the Red Strings. This cohort regularly plays events like the Waterfront Blues Festival, the Montavilla Street Fair, and Pickathon, but they get in at other venues only as age restrictions allow.

Spots like the Hawthorne Theatre and the Crystal and Wonder Ballrooms host both all-ages and 21-plus shows. But OLCC (Oregon Liquor and Cannabis Commission) code requires expensive increased staffing when serving alcohol if minors are present, and mandates cordoning minors to balconies or a fenced-off section of the floor. What’s more, booking these venues typically requires the clout of agents, publicists, and record deals.

Many under-21 upstarts turn to the beloved-if-uncontrollable house show, not necessarily aboveboard or entirely public, but often more approachable. Middleton admires such “daring and chutzpah” but doesn’t see the residential workaround as a sustainable answer for Friends of Noise, and opening a bar is compromise too far. “A true all-ages space should be centering the young people and the music,” he says, not “the sale of alcohol.”

Friends of Noise moved into the Dancin’ Bare building in December and is looking to open in June. Fundraising to cover rent and buildout costs is ongoing, but substantial contributions came thanks to community drives and grants from Prosper Portland and the Oregon Cultural Trust. The poles were already gone, and the strip club’s iconic sign will move to a new home. Beyond that, the conversion to a 400-capacity concert hall meant a different kind of stage, ADA-compliant features, and a viewing platform for wheelchair users, as well as a recording studio, office space, and a green room—there’s even an on-site screen printing rig for making merch.

A Friends of Noise venue has been a long time in the making. But Middleton turned down several prospective sites before finding one in a neighborhood outside the city center, to serve kids and adults in lower-income areas. The Dancin’ Bare was “a godsend,” Middleton says, because it’s on the MAX line and “literally halfway between Jefferson High School and Roosevelt High School.”

Without alcohol sales, the business plan calls for a system of sustainable donations, with local businesses encouraged to sponsor $250 annual passes, which kids can then apply for. Parents and individuals can also purchase passes, which grant admission to three shows per month. With a goal of selling 1,500 passes a year, the group could pay artists and production crews whether passholders show up or not. Not that attendance has ever been an issue at Friends of Noise shows. Minding the lack of booze, the vibe is less talent show than underground, kombucha-serving nightclub.

When the Off Beat opens, these fleeting highlights will be a constant addition to the city’s music scene, an addition where those under 21 won’t be sequestered in a sad nondrinking section or, worse, listening from the street. They’ll mix into the crowd, friends of the band.

Share this content:

Post Comment