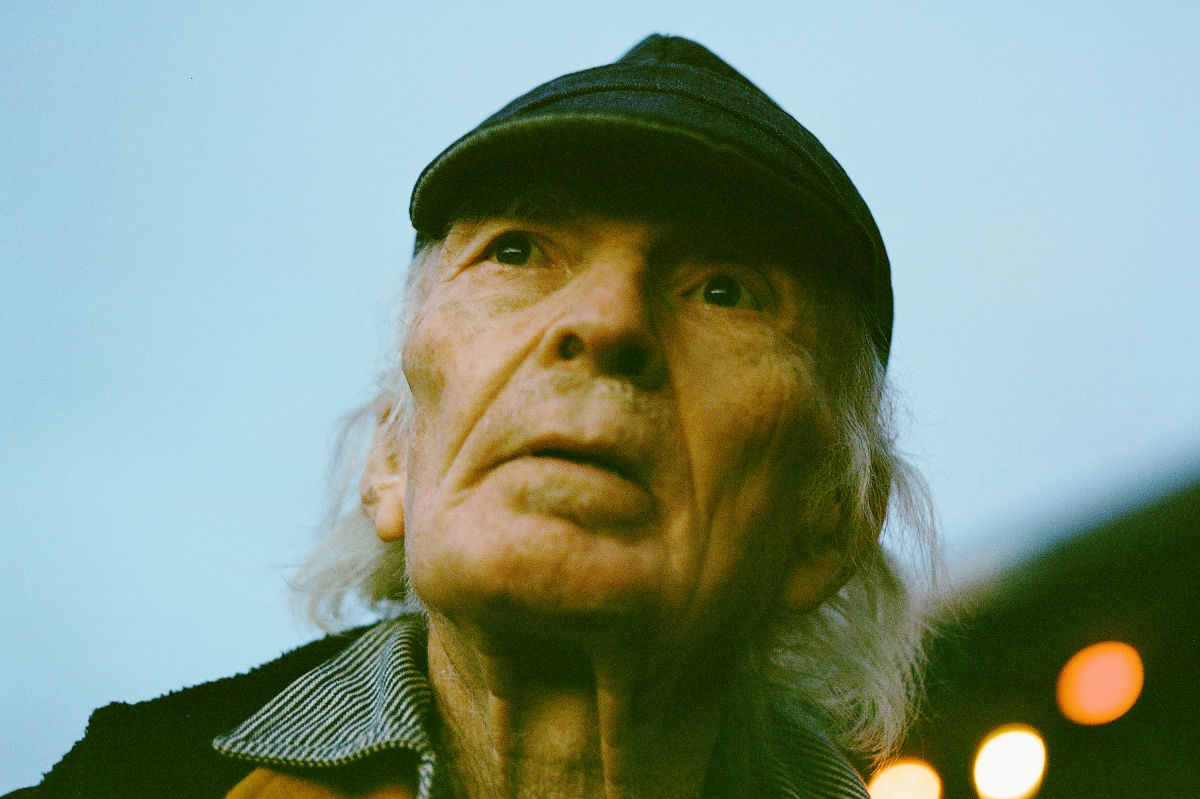

Michael Hurley Was the Folk Hero of Portland

The late songwriter got his start in the Greenwich Village folk scene of the 1960s but landed in Oregon in the early 2000s.

When news broke in April that folk musician Michael Hurley had died, eulogies flooded the internet. Write-ups everywhere from Rolling Stone and Stereogum to NPR and The New York Times were appreciative if a bit circumspect, leaning on words like “eccentric” and “outsider.” Things were more intimate on social media. On Instagram The New Yorker’s Amanda Petrusich remembered Hurley as “one of those singers who was so genuinely singular & idiosyncratic & pure, it felt lucky just to share air with the dude.” The band Big Thief shared that Hurley had written “some of the most heartacheingly beautiful melodies of all time.” M. C. Taylor, of Hiss Golden Messenger, described Hurley’s music as embodying “America as I like to think of it, like a Joseph Mitchell story, everything good and goofy and sad about whatever it is we’re doing here.”

Hurley lived in Brownsmead, by Astoria, but Portland was his regional home base the past few decades. He was a foundational artist for locally founded label Mississippi Records and for years kept a monthly gig at the LaurelThirst, playing a happy hour set with his band the Croakers. Like a lot of people, I was lucky enough to see some of these shows but foolish enough to not have seen more. The last time I saw him perform, at Southeast Portland’s Showdown in December 2024, weeks before he turned 83, he held a capacity crowd in absolute rapture for 90 minutes, then walked across the venue to go work his own merch table.

In early May, hundreds of friends, fans, and family members gathered in Sumner-Albina Park—across the street from Mississippi Records’ shop and the restaurant Sweedeedee, the latter named for a Hurley song—to celebrate his life and music. A stage had been erected and the whole park converted into a kind of Hurleyville. There were large handpainted reproductions of his artwork: the impish beatnik wolves Jocko and Boone, a red roadrunner with a white beak, some long-snooted space aliens, plus blueberries, cacti, crows, and more. (Hurley created all his own album art as well as comics and zines.) Volunteers served chili, corn bread, and fresh pie, all references to his work. (He was, among other things, one of the great bards of the appetite.) Joints and sage bundles smoldered. Someone set up a Grateful Dead–style taping rig. Lindsey Nevins, a tap dancer who was sometimes part of Hurley’s percussion section, reminded the crowd, “We’re sad but the songs aren’t sad. We miss him. Let’s party.” For the next four hours, with the Croakers as house band for the 50 or so musicians who had come out to play Hurley’s tunes, that’s what we did.

There was no shortage of songs to choose from. In 60 years as a working musician, Hurley released around 30 albums, nearly all with independent labels or self-released. He got his start in the Greenwich Village folk scene of the 1960s and had early champions in Jesse Colin Young (later of the Youngbloods), Peter Stampfel of the Holy Modal Rounders, and Moses Asch, the revered founder of Folkways Records. Hurley’s often cited as one of the founders of “freak folk,” which is true as far as it goes (it’s hard to imagine Devendra Banhart, Joanna Newsom, or Bonnie “Prince” Billy without his example), but the tag sells him more than a little short. Nathan Salsburg, former curator of the Alan Lomax Archive and a brilliant guitarist himself, told me that Hurley’s “guitar playing, like his songwriting, is an untangleable synthesis of American vernacular styles, and was honed as finely as Joni Mitchell’s or Richard Thompson’s, who are equally instantly identifiable players. I am sure that I’ll never know anyone ever with Michael’s consistency or singularity of vision.”

Rock critic Robert Christgau once described Hurley as an “old-timey existentialist, whose oblique wail recalls both Jerry Garcia and John Prine.” This was loud and clear in the first Hurley song I ever heard, “Hog of the Forsaken,” when it played over the closing credits of an episode of Deadwood. The screwy saga of a swine that gorges on the bodies of fallen angels is built around an earworm fiddle riff and a melody so distinct yet unplaceable I assumed it was one of those authorless songs brought over from Olde Europe and left to ferment for a century or two in the Appalachians. I had to hear it again, so I tracked down a copy of Long Journey (1976), and was surprised to discover that “Hog” was Hurley’s own composition. The album—which contains such classics as “Portland Water,” “You Got to Find Me,” “Watchin’ the Show,” and the title track—made an instant convert of me. I started to explore his vast catalog and soon realized I already knew several Hurley songs from covers by Yo La Tengo, Cat Power, Vetiver, and others.

The list keeps growing. Choice covers of recent vintage include Kassi Valazza’s “Wildegeeses,” Cass McCombs and Steve Gunn’s rendition of “Sweet Lucy,” and Espers’ “Blue Mountain.” During the pandemic, a Nashville-based indie rock band recorded a full-length, Styrofoam Winos Play Their Favorite M. Hurley Songs. The Winos’ LT Turner told me that when they sought Hurley’s blessing to release it on Bandcamp in 2022, he not only gave it but asked their permission to burn some CDs of the record to sell at his shows.

Hurley’s cosmology is weird and dreamy but always attuned to earthly concerns: food and drink, lust and love, plants and animals, road trips and car repair. He’s also very funny. In “Open Up (Eternal Lips),” spiritual yearning is felt as a kind of horniness: “Well it’s just a little bit where I’m feelin’ kinda naughty / Take me to the tit of the heavenly body / Open wide, let me slide / To sweet by and by.” Even a gorgeous, tender love song like “O My Stars,” which Hurley was often asked to perform at weddings, devotes an entire verse to a spider crawling up a wall “to get his ashes hauled / He taking that trip along the mighty top / He learning them ladies the old spider rock.”

My favorite of Hurley’s more recent songs, “Clatskanie,” has a refrain so simple that the first time I saw him perform it, at the Aladdin in 2023, I thought he was making it up on the spot as a goof. It goes, “Cook fish / bake pie / down the road / Clatskanie.” He sang it over and over, the repetition beguiling and hypnotic. It dawned on me that he was in earnest and that I was having a deeply moving, even quasimystical experience inside the spare, vital world conjured by the song. Crucially—and this is perhaps the essence of the Hurley magic—my revelation of seriousness did not make the song any less fun than it had been when I’d thought it was just a joke. “I like original music,” Hurley said in a 2021 interview. “I like to listen to people who are playing themselves, not somebody else or who they think they should be. I like a raw truth. I like to celebrate the hilarity of life. The whole deal.” These are words to live by, and he did.

Share this content:

Post Comment