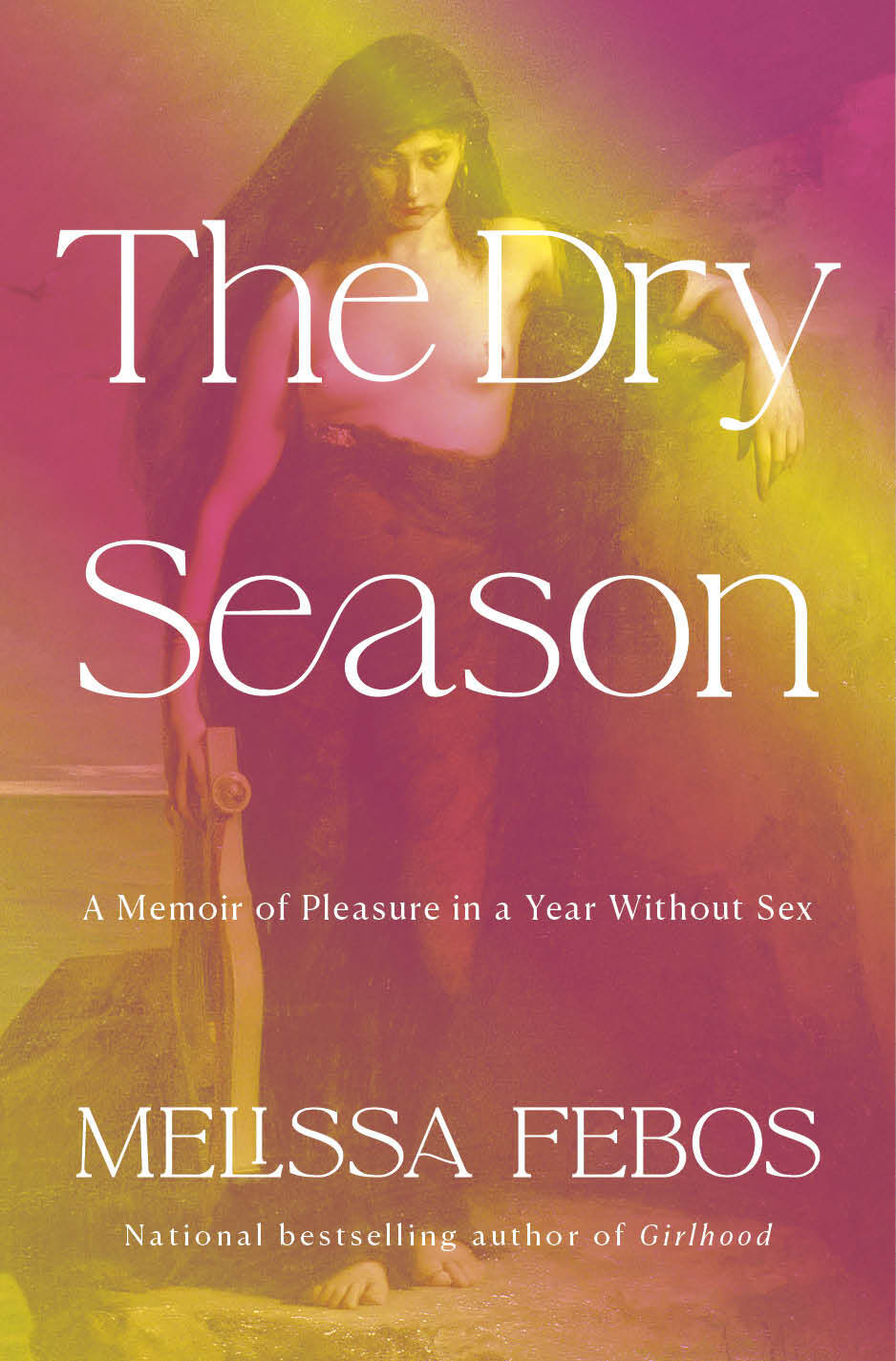

Melissa Febos on Her Year Without Sex

In her latest memoir, The Dry Season, Febos details her motivations for spending a year celibate, and what she learned while doing so.

Melissa Febos is not a sex columnist. Nor is she some kind of public-facing therapist. Her books—the fifth of which, The Dry Season, is out this month—aren’t self-help books, either. Far from it. Since her 2010 debut, Whip Smart, a memoir of putting herself through college while working as a dominatrix, Febos has been a literary critical darling, a best-selling author, and a Guggenheim fellow. Her memoirs and essays are art, free of any obligation to serve up life hacks, breathing exercises, or nifty conversational tactics. And yet, toward the end of our interview, I confessed I was struggling not to warp my questions into queries for personal advice. She laughed and asked, “What is it you’re wondering about?”

Whether or not you’ve been a dominatrix or spent a year intentionally celibate (the premise of her latest book) is sort of irrelevant. Febos is a master of adapting wisdoms gleaned from her own unique experience. She renders them on the page with a stunning, approachable, and readily applicable clarity, often juxtaposed with feminist art and literary history. I didn’t have a specific “Dear Melissa” conundrum. I was most interested in the tension inherent in making art with such a practical use built in. “I am an artist, and a huge part of the work of writing a book is aesthetic work. But I am also doing that work because it changes me and makes my life better,” Febos told me. “It would be ridiculous for me to deny that.”

Over Zoom, we talked about why one might willfully stop having sex, the difference between solitude and loneliness, and the contradictions of writing memoir, and tried desperately to avoid describing the year Febos spent abstaining from romance as a “journey.”

Febos will read from The Dry Season at Powell’s Wednesday, June 4 at 7pm and chat with Portland novelist Chelsea Bieker.

MT: On a flight to Portland in 2016, you’re reading May Sarton’s Journal of a Solitude.

MF: [laughs] That’s right.

MT: The first sentence of which is, “Begin here.” You took those instructions pretty literally. Sarton’s second sentence is, “It is raining,” which you used as both the first and last sentences of this book. What does it mean to give those crucial points of your book to another writer?

MF: I wanted to place and present [the book] within a larger lineage of artists and people who were struggling with the same things I was struggling with and striving to find a way to live within and beyond them. That is so much the project of this book, and it was such a hallmark of that year. I found myself again and again in the words and experiences and art of other people.

MT: Why start and end a book about a year of transformation with the same sentence?

MF: I’ve realized over and over writing memoir, and writing from personal experience, that the story just restarts. As soon as I have that feeling of accomplishment, or [feel that] I’ve arrived somewhere, it just starts over. There’s a new application for the things I feel so accomplished in having learned or mastered or progressed my thinking in. So [it’s] also a nod toward the ongoingness of a life story and the ongoingness of the work that I depict in this book.

MT: Sarton writes about trying to get to her work before using up all of her energy on other people—coming to writing with “freshness and zest.” You write about a similar impulse, or struggle, following a stormy two-year relationship that you call “the maelstrom” here, which was the subject of your book Abandon Me. You were 35 at that point, right?

MF: Yeah, yeah.

MT: Was that a new desire at 35, to carve this space for yourself?

MF: I had a pretty regular tradition of going to residencies or on retreats and sort of leaving my life in order to do my work. But I never characterized that to myself or anyone else as a desire to escape my partners or my own patterns in relationships. I had never taken a break from romantic engagement and activity, even though many people had suggested it to me over the years. I have to be in pretty extreme pain to change something that I feel dependent on. And I think I had hit that point.

MT: Something’s gotta—

MF: —yeah. The pains are outweighing the benefits.

MT: So when you start this celibacy journey—god, I said “journey.” Sorry.

MF: It’s totally fine. It’s unavoidable. I find myself saying it all the time, and I cringe every time.

MT: I felt it coming out and I couldn’t stop it.

MF: Earlier today I swapped in “path,” but that felt almost as cringy.

MT: We’re in this together now, I feel more comfortable. So, early in your celibacy—I think I can just say celibacy?—everything is sort of optimized. Your head is clearer and you’re doing everything you struggled to manage before. It’s almost a life hack: If I just don’t think about flirting or sex or pursuing romantic interests, I can do everything else.

MF: Yeah.

MT: And then you’re getting off a plane, and you have this muscle memory thing to check your phone.

MF: Mhm.

MT: To write to whoever’s supposed to be waiting to hear that you made it safe.

MF: Mhm.

MT: But there’s nobody to text. Agency is the easy answer to the question of differentiating between solitude and loneliness. Yet, here you’ve created this solitude for yourself, and you feel this loneliness creeping in.

MF: So many of the sort of projects of my life are trying to navigate competing impulses. People always think, because I write memoir, that I’m, like, into self-awareness. But I am not. I hate it. There’s a huge part of me that just wants to watch TV and eat candy and smoke cigarettes and, like, never have an intimate conversation and never feel a feeling. Let’s not look down there, you know? Most of me didn’t want to change, and didn’t want to be alone, and was very happy with the incredibly limited cycle of seduction and flirtation: having a secure sort of partnership for a while and then blowing it up and starting all over. It’s exhausting and thrilling and horrible, but it’s predictable. I could have just done that for my whole life. A lot of people do.

In those moments of loneliness, there would be a little thread of terror, where I was like, “Oh no, what am I doing? I’m alone in the world.” And then it would pass, and I would go back to really enjoying being alone in the world, because it turns out I was kind of starved for that, and I actually loved it.

MT: Why did you work so hard not to label your relationship to love and sex as an addiction? For much of the book, you’re kind of battling yourself, adamant that this isn’t an addiction, but also spelling out how it looks a lot like your own experiences with substance abuse.

MF: The relationship I described in Abandon Me, the bottom I hit that prompted me to spend this time celibate—I think I could characterize that relationship as a kind of addiction. It mapped directly onto my experience of addiction: I felt really powerless, I sort of became a stranger to myself, and it created a lot of wreckage in my life and other peoples’ lives. But not all of [my relationships felt like that].

I wanted to think very critically about the ways [the] sort of the story and script I was working with was not inherent to me. It was something that I had inherited from centuries of heterosexual economies, you know, and also just a persistent characterization of love that is promoted, mostly through capitalistic channels, to try to sell us stuff and have us watch stuff. Love was supposed to be this very intense, thrilling thing that happened to you. You were kind of a willing prisoner of it, and then you got married, and it was the end of the story. That wasn’t a product of my addictive personality. That was like the soup that I was raised in. I had the question of, like, How do you forge and define a healthy, conscious relationship to something in a society that has a sick relationship to it? Who are the people who have done that? And how might I do that?

MT: You have this line about how you could, “communicate my sexual identity through the set of my shoulders, if need be.” Early in life, you realized you understood seduction better than most. But when you stepped outside of it, you started seeing it in other people. Your friend Ray tries to seduce you, and you’re like, “This is what this looks like?” Another friend, you write, “opened every door like it was the door to her bedroom.” You’re laughing at these people, and at your past self, because you kind of see the game for what it is when you’re not playing it.

MF: We’re living in a story that we’re constantly writing about ourselves, and I think what other people see is actually very different. They have access to a lot of information that we don’t know we’re revealing. Not only did the machinations become visible to me in kind of an embarrassing way—Oh, this person is trying to seduce me; that’s hilarious—but also the investment of the seducer became really clear, that it had very little to do with the other person. It was a kind of transactional gesture, and it was also, in a lot of cases, a form of manipulation, to varying degrees of nefariousness.

MT: You land on this Audre Lorde essay, “Uses of the Erotic,” and quote her talking about breaking these recurring patterns instead of “settling for a shift of characters in the same weary drama.” What does that mean in practice?

MF: You know, I met my future wife shortly after that year ended, and we started our relationship really differently than I ever had. I foregrounded things that I had elided about myself in other relationships: I need a lot of alone time, sometimes my friendships and my work are going to come first. I want to be in a relationship where we’re very differentiated and we support all of the other passions in the other person’s life, even if that means that we’re not the first priority.

MT: Hildegard of Bingen is a pretty big figure—in the world, but in your book, particularly. Her work seems to be a bridge between a higher power and art making and, if not sex, profound sensual experiences. And I think those three things converge a lot for you in making art. Does it matter if you separate them? It gets fuzzy, I guess.

MF: Yeah, it does. And I see that as a good thing. It’s a symptom of the way we live, of capitalism, of the human desire to have things in tiny little categories. We talk about our sex life and our work life and our marriage and our creative life as if they are all discrete. And no one, of course, has enough time in a life to have that many lives.

When I stopped having sex, suddenly I experienced this profoundly vivid and sensual aspect of experiences that I just hadn’t thought of as erotic—like the way the air feels in New York in late summer. It’s kind of gross but beautiful and fecund. Hildegard was incredibly in touch with that. I think she led an incredibly sensual life. I write in the book about how she supposedly wrote the first description of the female orgasm. I don’t know how she classified that. I don’t know how she experienced it. But I think that wasn’t the definition of sex at the time. Sex was something you did for your husband to have babies. It was a way to serve men.

MT: In the book, you point out the different motivations women would have historically had to choose celibacy, contrasting your reality, as a woman in twenty-first century America with, say, Hildegard’s, who lived in the twelfth century, in medieval Germany.

MF: If you had asked, “Do you think you are operating in kind of a patriarchal relationship model?” before this experience, I would have been like, “No, are you kidding? I’m queer, my partners are women. Ha! Ha!” But I think, to a great extent, I was. I was doing this work of self-erasure, self-minimization, or contorting as if I didn’t have a choice, as if there wasn’t room in my relationships. And there actually was, I think, in a lot of my past relationships. My partners were also uneasy about that behavior, and it created more problems than it was solving, but I wasn’t conscious of it, so I couldn’t stop.

Centuries of patriarchy have done a number on every single person alive. The women I was reading about literally had no other option. They couldn’t divorce. They had no rights. They couldn’t own property. It was illegal for them to live in many of the ways that I do. And they still managed to find a way to do it, and have what seem to me to be pretty rich, fulfilled lives.

Share this content:

Post Comment