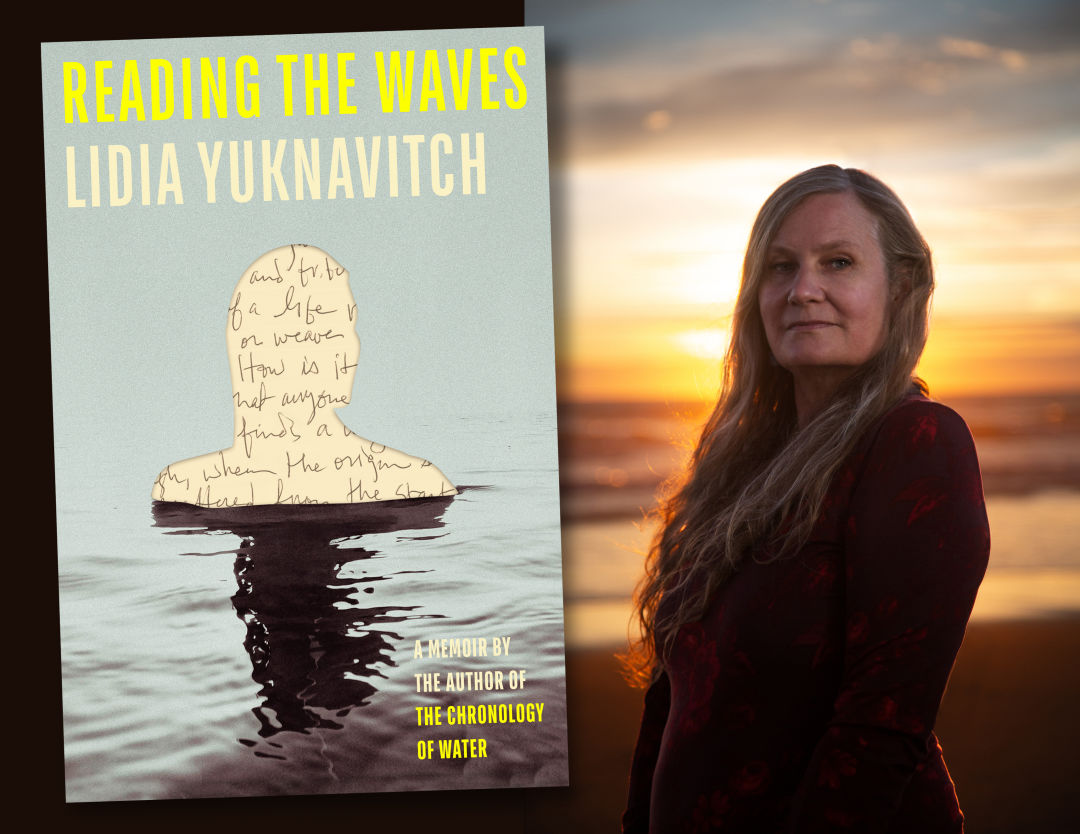

Lidia Yuknavitch, Kristen Stewart, and ‘The Chronology of Water’

Reading Lidia Yuknavitch is like taking in a painting. Everything in her novels and memoirs appears before you at once, and as the viewer—or in this case, reader—you’re free to pick up whatever threads pull you. And they will pull you. If I told you her writing is stream of consciousness, you likely wouldn’t think of, well, a stream, a spitting current, a geyser, or a fish-filled brook. Phrases like “making a splash” or “wading in” no longer force an image into your mind because water is a thoroughly exhausted metaphor. Yet somehow Yuknavitch, who has spent most of her career in Portland and now lives near the Oregon Coast, made her own language of water inspired by her early life as a competitive swimmer. In 2011, she published the remarkably affecting memoir The Chronology of Water, which simultaneously grapples with the most traumatic, liberating, and sexually charged moments of her life. Kristen Stewart is currently adapting it into a feature film—an intriguing challenge considering the book is also a polemic against chronological storytelling. Nothing is linear in Yuknavitch’s world (water doesn’t move with the hands of a clock), and her history is constantly shifting. “I’m not talking about facts,” she writes early in Reading the Waves, her second memoir, out February 4. “I’m talking about what we do with events in our lives.” Like Stewart’s movie, Yuknavitch explained over a recent Zoom, this second book is a kind of adaptation of the first—not a corrective or disavowal, but a trip into her past to reframe and complicate the sea that is her story.

The responses I received to Chronology of Water opened up this, like, time and space portal. I stepped through, and all the other books kind of released after that. I’ve made writing swimming. I’ve tried to understand language as oceanic. Not to sound 100 percent woo, but it’s vast, and it’s moving, and it changes, and it has dead things in it and live things, and it moves in waves and it spits shit up on the shore. Every time I move toward writing in water, something different comes out. I can explain things to you if you let me talk about water; it’s not like it’s ever gonna run out.

Kristen [Stewart]’s project I have always thought of as autonomous to her. She’s making a piece of art that may have had a launching pad or a touchstone in a piece of art I made, which is cool; artists love to riff off each other, that’s our jam. That’s how it feels to me: far away, even though it’s intimately connected to me. [Reading the Waves] didn’t come out of that relationship at all. It was coming more out of, Holy fuck, I’m 60; it’s coming more from understanding change and age and stories. Returning to events that were difficult, that made you carry sorrow around, there’s a chance to stand in a different position to them. Not only could you shape-shift the story, but you could maybe shape-shift yourself, which I don’t think is some brilliant concept. It’s what we’re all doing all the time. I’m just fucking slow, and it took me a long time to understand that you don’t have to live these stories you’ve been carrying around exactly as you [first] embraced them.

I am obsessed with fairy tales and fables. They appear in all my novels. But closer to home, I just fucking love creatures like frogs, which, in the literal world, shape-shift. They’re also prominent in folk tales and fairy tales and fables in a magical way. They represent that we’re all under revision and dissolution and reassemblage all the time. We don’t think of ourselves that way unless somebody makes you, or you have a traumatic experience that shows you your own shit, and you’re like, Oh my God, that’s my own shit coming out. Butterflies are also a great example, because they go to goo. If you cut one open when it was goo, it would just be goo. But if you let it transmogrify, well, you know what butterflies start out as and end up as. The fairy tale/fable space is the magical version, but the literal version is just as true.

I don’t actually believe in linear time. Nor do physicists, so I have good company. I’ve come to understand [memory] just as story space. When I travel to memory, it’s not to that past event that happened all those years ago; it’s like being able to breathe and speak and travel underwater. I wrote a whole novel, called Thrust, about this girl who can time travel because she can breathe underwater—that’s the portal. So I made a fictive version of what I’m telling you now is my literal understanding of memory. But then I just start sounding, you know—people’s ears fold over when I start talking that way.

It’s really easy to ignore chronology and focus on how one experience [claps] snaps you back to something in your past or forward into the future. There’s no rule about it. It just happens. A certain smell or a song makes you a time traveler. It just does. Everybody knows what I’m talking about. I didn’t make it up. And I’m interested in going in there.

To go back in and find what was beautiful seems, to me, the only reason we have relationships. At some point you have to remember the beauty, and none of the rest really matters. I mean, we’re all going to the same place. And we’re all going to get there with scratches and scars and bruises. And we’re all going to do great things. And we’re all going to do shit things. It’s that idea of retrieval—retrieving what’s beautiful. And here’s why: so you can hand it to someone else in case they need it.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Share this content:

Post Comment