Kann’s Collaboration With Deadstock Has Produced Some Incredible Coffee

The Haitian restaurant Kann has become one of the country’s most sought-after dinners since opening in 2022; owner Gregory Gourdet, a multi-time James Beard Award winner and a Top Chef finalist, is now one of Portland’s most famous chefs. (He just opened five different food and drink outfits within the sexy new Printemps in New York.) Kann blends the nicest parts of an upscale experience with the familiarity of a neighborhood spot: Kids play Uno at the big tables while well-heeled diners take the two tops in style. And whatever you eat at Kann, you need to end the evening with a cup of “Kann coffee.”

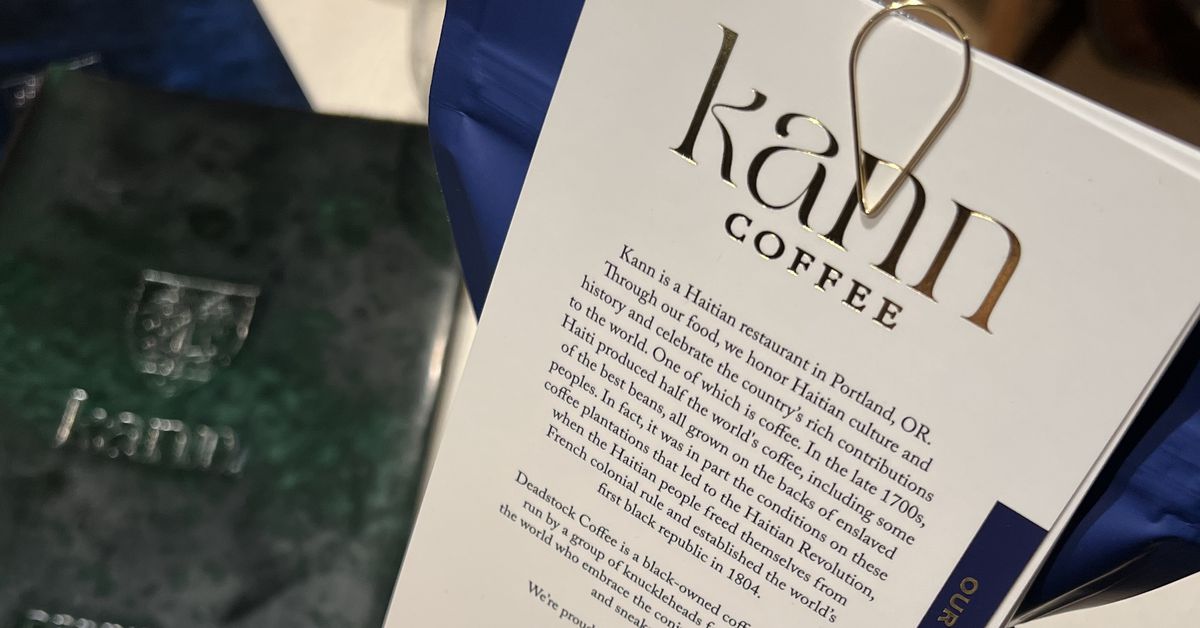

This special edition coffee is a collaboration with popular roaster Deadstock. Mixed in with the Haitian beans are cinnamon, vanilla, and star anise. The result is bright and fragrant. There’s a Cafe du Monde profile when one zooms out, but if the beans at the iconoclastic New Orleans shop were roasted by an old wizard who knew each bean by name. If guests are inspired by the coffee, they can buy bags of beans mixed with spices to take home, a souvenir that represents the partnership between two of Portland’s premier Black-owned businesses.

The partnership came about partly because of Gourdet’s personal interest in coffee, partly because of his friendship with Deadstock owner Ian Williams, and partly because Kann’s mission is to educate its guests about Haitian cuisine and culture, a lesson that would be incomplete without the inclusion of coffee. “Coffee is deeply intertwined with the history and culture of Haiti,” Gourdet said in a statement to Eater. “This industry was pivotal in the Haitian Revolution, which led to freedom from French colonial rule and the establishment of the world’s first Black republic in 1804.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25920213/KANN_COFFEE_RECIPE_CARD_SHOOT_020.jpg)

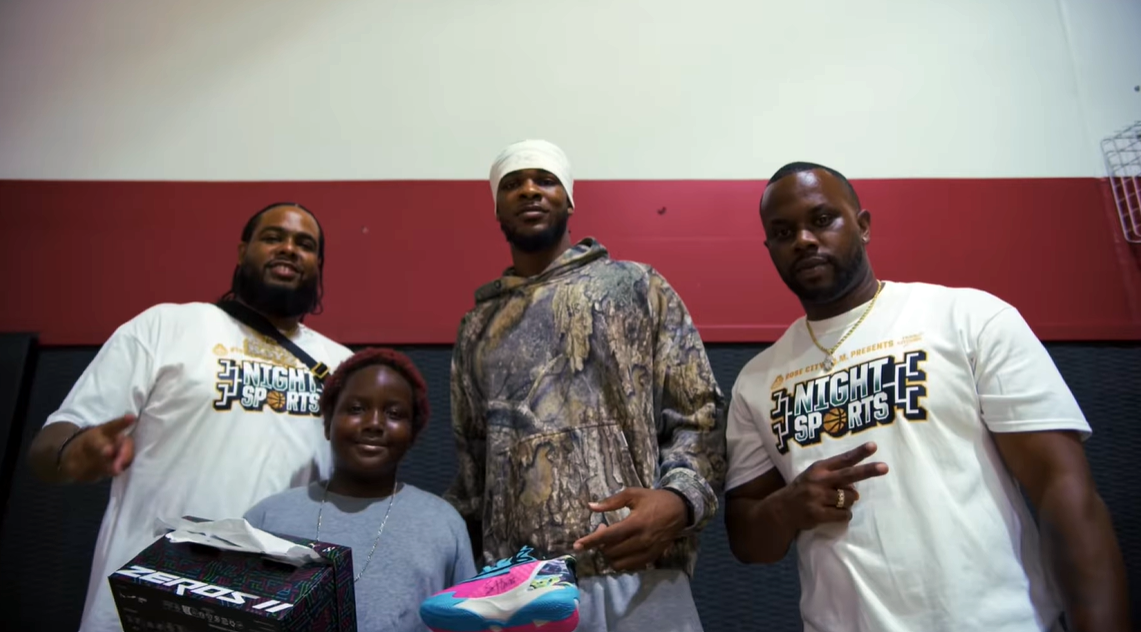

Williams says the partnership was a natural fit for him. His father was a chef, as was his sister for a time. He’s been friends with Gourdet for years; they and other Portland food and beverage industry friends would often vacation on the weekends and cook. “And he was telling me, ‘Whenever we open this restaurant, we want you to do the coffee,’” Williams says.

There was already a Haitian coffee in Deadstock’s portfolio before Kann opened. Williams brought that and six other coffees to Gourdet to try during the restaurant’s run-up, but Gourdet wanted a spicier, bolder flavor. Williams offered other coffees. They were too light, then too dark. Eventually he decided to let Gourdet try what he’d been experimenting with on the side: Southeast Asian-inspired riffs that included toasted rice and corn. Gourdet told him that was exactly what he was looking for. That’s how the coffee shots were served in the streets of Haiti.

He added anise, cinnamon, vanilla bean. Now Williams leads classes at Kann before dinner service to demonstrate how best to make this coffee and walk through the history of Haitian coffee. (Follow Kann Coffee on Instagram for news about upcoming classes.) “His Haitian culture is an important piece of what he does,” Williams says of his partner. “And, as Black men, we’re kind of killing it right now.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25920215/KANN_COFFEE_RECIPE_CARD_SHOOT_035.jpg)

Another reason this partnership is important would be Haiti’s singular relationship to coffee production. The country’s historical relationship to coffee follows the story of its liberation — it produced a majority of the coffee consumed in Europe in the late 18th century, but after the Haitian Revolution (the only successful slave revolt in history), the country’s infrastructure was wrecked and it was in massive debt to France. Haitian coffee production never recovered.

But Haitian coffee is on the heat map today. A few years ago Barista Magazine noted specialty Haitian beans scored a 92 at Portland Coffee Fest 2021, a first for the region. But Haiti is still struggling: Gang warfare in the country has become a crisis, according to the United Nations’s representative to the country. This winter, the United Nations reported that more than a million citizens were displaced while various factions vie for control of the country’s capital, Port-au-Prince, Gourdet’s family’s homeland.

“Haiti is going through some serious stuff,” Williams says. “We have to have real conversations about that. And it’s way better that it comes from us and not from white people.”

Share this content:

Post Comment