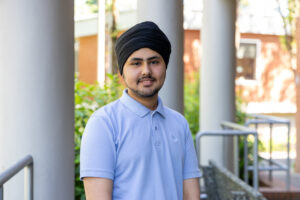

Jess Ackerman: Between Making Art and ‘Making It’

Ackerman’s latest show, Love Notes from the Lurker, at Chefas Projects in May, marks a distinct turn in the artist’s life and work.

A lot of life happened to Jess Ackerman in 2023. That February, the rising-star Portland painter had their first solo show outside the city, at Glass Rice Gallery in San Francisco. Just four months later, they had another at the local gallery Chefas Projects. Messy, exuberant scenes filled both—of dirty dishes, all-too-joyous layer cakes, cigarettes, house plants, and wine bottles that glinted with cartoony, star-shaped highlights. Titled A Raw, Biodynamic, Grass-Fed Paradise and Always Been the Laughing Boy, respectively, these two outings established Ackerman’s voice as a playfully ironic and poignantly melancholic still life artist. Coincidentally, the career high point also preceded Ackerman’s gender-affirming top surgery, which, after years of delays, came in August.

Though the shows went well, being the center of attention felt differently than Ackerman expected, if they’d had time to do much expecting. As in their paintings, something lurked beneath an outward presentation of ease. The surgery itself went according to plan, but two weeks before it was scheduled, Ackerman’s insurance changed their policy and refused to cover the costs. Still, friends set up a GoFundMe and, relatively speaking, eight months in, Ackerman’s extraordinarily busy and transformational year was going OK. They’d managed to carve out a career as a working artist, left their barista job behind, and were meanwhile on the way to feeling more comfortable in their body. Why didn’t it feel like it?

“The still lifes end up being memories,” Ackerman told me at their studio in April; the paintings help them make sense of the recent past. “So many people use humor to mask or get through things that are hard—that you don’t maybe have time to process, like, presently, as it’s happening to you.”

They had about 20 paintings on their small studio’s walls when I visited. The finished ones were on the left, with others at various stages of progress as you moved to the right. A solo show often contains a year or two of work. Which means that these paintings, made for Ackerman’s upcoming show, Love Notes from the Lurker, at Chefas Projects (opening May 9), are roughly on pace with the art world calendar. Two years is a lot longer than the four months that separated their last two shows, but that gap isn’t for lack of opportunities. Ackerman burned out in 2023. The inchoate dream they seemed to be manifesting, of “making it” as an artist, turned painting into a chore. “It was horrible,” they said. So they stepped back, took a job at a coffee shop for a regular routine and paycheck, and slowed their painting practice, showing in several group shows instead of making a larger body of work.

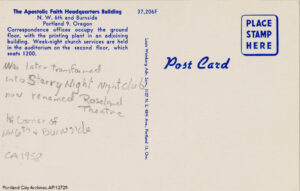

Two years later, diving back in looks different. This show’s title plays on the online slang for a nonparticipating observer. A lurker is present but not involved. Instead of painting mostly from their own life, as they did previously, Ackerman’s gaze has moved on to the lives of others. A few of the new paintings are abstractions of photos they took walking around at night, looking into windows, at people’s gardens, simply observing from a distance. Ackerman said this felt like “looking at our friends’ lives on our phone.” Friends, they added, intoning scare-quotes, “that we don’t see for years.” In both scenarios, our impressions come from context clues and projections rather than actual interaction.

“I love this,” they said, smiling as they gestured toward an intricately patterned painting with a small Felix the Cat head at the bottom. “It’s so disturbing.” They showed me a picture on their phone of a sliding glass door shaded by a tall plant with a little Felix toy in the corner. It was of a house they sometimes walk past, though “not a real house,” they explained; it’s too big, and seems to be a weed-growing operation. “No one lives there.” In the painting, the plant became a quilt-like pattern. Felix was the only obviously representational element. Nevertheless, the photo’s voyeuristic overtone transferred to the canvas.

People rarely feature in Ackerman’s paintings. They’re often of fruit bowls, tulips, a few dogs here and there. Most of the current paintings are even abstractions of these nonhuman forms. Yet the paintings are hugely personal. The scenes—memories—function like snapshots in the wake of life, conjuring an appreciably specific moment: These aren’t just things, they’re someone’s things. In the recently translated book The Use of Photography, by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie, Ernaux writes of a similar impulse to catalog the shambles of her own life, describing a morning-after mess of clothes as “the only objective trace of our pleasure.”

The joy and pleasure in Ackerman’s pictures are genuine, too. And not despite, but because of the troubles they communicate. It isn’t a mocking celebration of impossibly wonderful things, like flowers that seem to dance, and cakes that tower like houses, and orange slices that steal you back to kindergarten soccer games. It’s a complication of these hallmarks, a contextualization, an emphatic both-and. Life—Ackerman’s and yours too—is beautiful and awful, and always at the same time.

With Lurker, Ackerman is pushing their stylized still life paintings further toward abstraction.

This is a particularly difficult sentiment to carry when discussing gender, especially during an administration mercilessly devoted to binaries. Bigots against gender-affirmation often reduce the entire scope of care to a binary, something that neatly and wholly moves a person from one identity to another—male and female for those with the smallest minds. For Ackerman, who is nonbinary and describes their gender as distinctly in-between, as well as many, many others, this couldn’t be further from the reality. The emotional and psychological results of gender-affirming care aren’t often so cleanly articulated, either. “Surgery helped me feel more like myself,” Ackerman says, “but I don’t feel some kind of queer joy.” It wasn’t a cure-all—gender is among life’s many challenges, and bodily presentation is only one aspect of gender—and Ackerman isn’t interested in saying otherwise to make a political point. “I just feel a little better, you know?” they said, affecting a muffled-trumpet voice before letting out a laugh. (“So many people use humor to mask or get through things that are hard.”)

On the in-progress wall, several of Ackerman’s paintings had neat rows of green tape marking a border around the edges. The designs vary significantly, and they’re more integral to the compositions than, say, something rococo and swirly, but painting in some kind of frame has become a signature. It grew out of not being able to afford wooden frames, and not realizing that painting them in is uncouth in some circles (“Oh, it’s cool that you just, like, don’t care,” is a backhand compliment peers have offered). But the painted borders have a function. “It feels like looking in the window, or looking in the phone,” Ackerman says. Painting a frame into the pictures removes them from reality, puts them somewhere else, Ackerman says, makes them “not a real thing.”

Share this content:

Post Comment