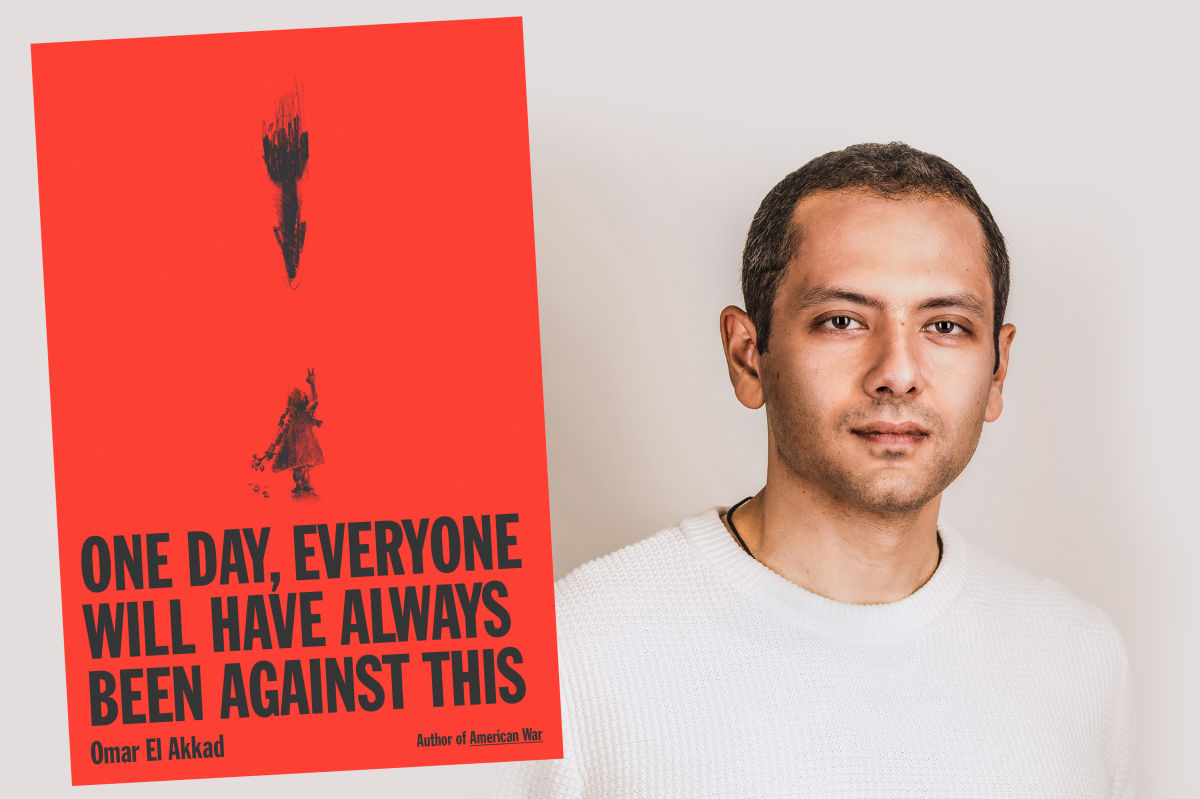

Book Review: Omar El Akkad Undresses American Propaganda

Titled after his tweet read by more than 10 million people, El Akkad’s latest book pits his personal experience and international reporting against American mythology.

Perhaps you’ve seen it, the famous line, “I don’t know how to explain to you why you should care about other people.” A week before Donald Trump first took office, in 2017, romance author Lauren Morrill tweeted the sentence in response to his demand that Congress repeal the Affordable Care Act. A version of it has floated around the internet since, and was frequently misattributed to Anthony Fauci during the pandemic, a time when the young and healthy were asked—even begged—to help protect the vulnerable. These days, some might call it a cry in the wilderness.

This same sentiment guides Omar El Akkad’s remarkable new book, One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This, which itself grew from a tweet seen by more than 10 million people. Days into the bombardment of Gaza, El Akkad’s message prefaced a video of the decimated city. “One day,” he explained, meant a day “when there’s no personal downside to calling a thing what it is.” Like Morrill’s, El Akkad’s words functioned as both a call to awaken and an indictment of silence in a time of atrocities.

A Portland resident for the past decade, El Akkad grew up in both Arab and Western cultures, in Egypt and Qatar, then Canada and the US. This broad life

experience gives his award-winning journalism and novels American War (2017) and What Strange Paradise (2021) a distinctly informed perspective on world events. Early in the new book, he recounts an experience his father had in Egypt in the early ’80s during a period of martial law that followed the assassination of President Anwar Sadat. A soldier demanded his papers, then tore the precious documents in two without a look and repeated, “Your papers?”

“It has been, for as long as I can remember, the memory that anchors my overarching view of political malice,” El Akkad writes of his father’s story. “Rules, conventions, morals, reality itself: all exist so long as their existence is convenient to the preservation of power. Otherwise, they, like all else, are expendable.”

This is the book’s core question: Who and what are “expendable,” and how do so many of us justify this expense? El Akkad draws a bead on America’s romantic image of itself as the defiant rebel, and as a nation that holds equality as a fundamental human right, while arguing the US has become the very thing it revolted against: the British Empire. How such a self-deluding system works, he goes on, is that while, say, the pioneers are slaughtering Natives, true dissension or resistance is not tolerated. But in time, it becomes possible, even virtuous, for the victors to claim solidarity with the oppressed. It’s inspiring to see Kevin Costner dancing with wolves, uplifting to see Disney’s John Smith fall in love with Pocahontas. Safely vanquished, the “savage” is ennobled. In other words, whatever the war crime or brutality, one day, everyone will have always been against this.

El Akkad is not an Arab apologist, nor does he excuse aggression. He calls the events of October 7, 2023, in which Hamas fighters killed 1,195 people, including 815 civilians, and abducted over 250 people, a “rampage, murderous and largely indiscriminate.” He describes Israel’s response in similarly graphic detail to articulate its “quite literally uncountable” death toll. The tens or hundreds of thousands of people killed by Israeli forces, with just as many missing in the rubble or diseased and starving, El Akkad writes, are not victims of retribution but evidence of an occupying force bent on the “expulsion or else extermination” of a people.

Though it bears witness, the book isn’t an accounting of genocide and its carnage. Instead, it lets this moment in history exemplify the hollow pretext of Western liberalism and the betrayal of the just and progressive agenda it pretends to stand for.

Central to El Akkad’s argument is an undressing of journalism itself. He spent 10 years as a reporter at The Globe and Mail, Canada’s newspaper of record, and challenges the idea that a reporter must be a neutral “referee” and at the same time agitate against silence. This gamified approach, he argues, centers polls instead of the impact of policies themselves. Holding journalists to an impossible objectivity forces reporters to “pretzel their way to a level playing field.” And this illusion of unbiased scorekeeping, El Akkad continues, becomes an alibi for covertly advancing agendas.

For example, in 2023, when Russia accused Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich of espionage, Western media accurately reported his conviction as a sham. They were able to do so because the events aligned with the Western narrative of an untrustworthy Russia. However, “as the Israeli military wiped out both Palestinian journalists and their entire families in a deliberate campaign to silence the flow of information out of Gaza,” El Akkad writes, the same media reverted to scorekeeping because the facts conflicted with US support of Israel.

“[J]ournalists themselves cannot call for justice,” El Akkad writes. “Except when they can.”

In chapters labeled “Witness,” “Values,” “Resistance,” and “Lesser Evils,”

El Akkad further explores the prevarications of Western culture through personal anecdotes. At a faculty event, a university professor yells at him for supposedly trying to get readers of American War “to side with terrorists.” Responding to El Akkad’s award-winning coverage in The Globe and Mail of a suspected terrorist group dubbed the Toronto 18, a reader comments, “I don’t trust any story about terrorism written by a guy named Omar.”

El Akkad persists, writing from this place of cognitive dissonance, like a sword slicing through smoke, revealing the ways we are trained to not-see unpleasantness, to avoid discomfort, to turn away from inconvenient realities. He reminds us that caring about other people might not cost as much as you think. Reminiscent of Orientalism, Edward Said’s influential critique of the West’s propagandistic view of the East, Against This depicts the invalidation of human life with searing clarity. “What does unlimited fear cost?” El Akkad asks in a late passage. “What will sate it?”

Share this content:

Post Comment