A Case for Portland’s Old Town–Chinatown Neighborhood

My grandmother’s earliest Portland memories taste like kalamata olives and wonton soup. She grew up in the Northern Hotel at NW Second and Couch, operated by her great-grandmother Sumi Akamatsu, who had previously run the nearby Mikado Hotel and bathhouse. My grandma would catch savory wafts of chop suey sizzling at the Republic Café or the steam from Wong’s Laundry on her way to school, where she’d play and study with a diverse group of students from Chinese, Japanese, Greek, and Black families. This was in the 1940s, a time when the area was a lively, dynamic home to immigrants from all over the world. Today, that neighborhood is known as Old Town.

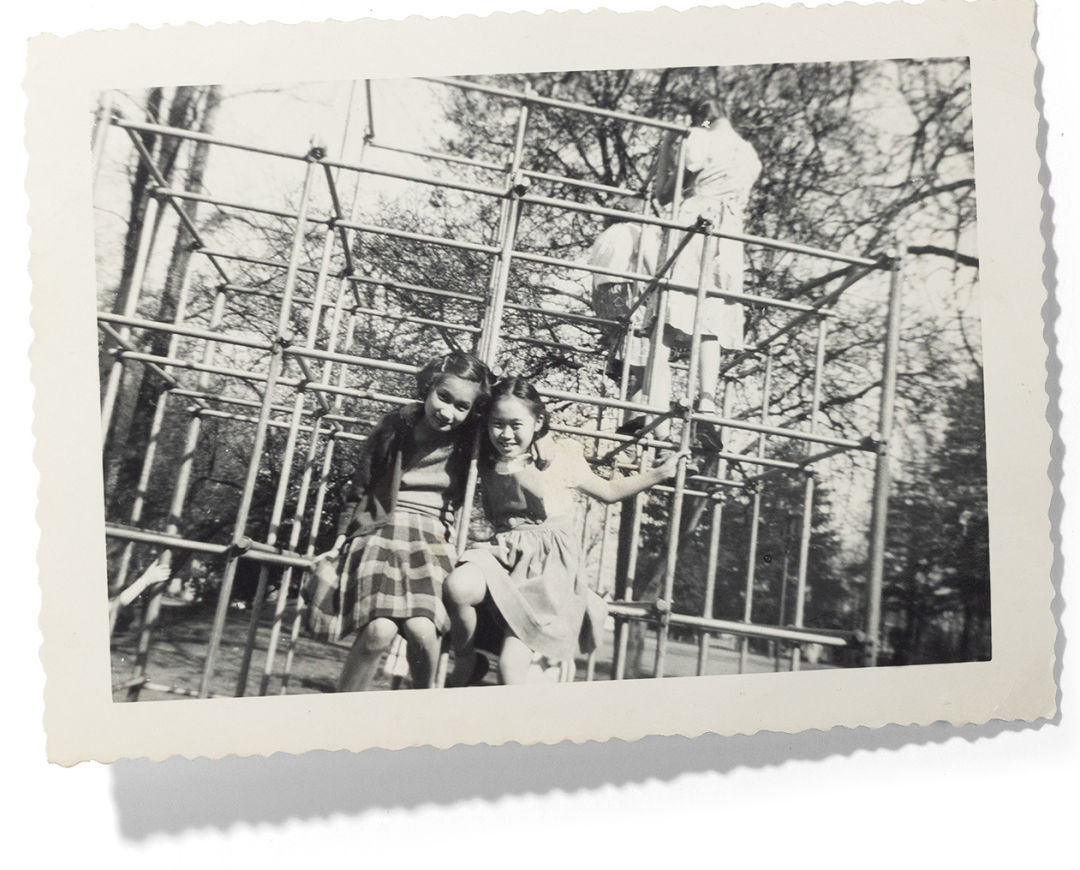

Joni Nakayama Kimoto Reeves (right), the writer’s grandmother, with friend Pat Lee at the Couch School playground in 1948.

Her memories of Old Town, this thriving cultural melting pot, contradicted everything I heard about the area when I moved to Portland in 2013. “Portland’s Iconic Old Town Chinatown Is Overflowing with Human Shit,” screamed a headline in Vice. An episode of Nat Geo’s Drugs, Inc. described the area as “the homeless mecca of US youth,” using choice shots to paint a portrait of a dilapidated, drug-dominated slum to avoid at all costs. My grandmother’s Old Town also added nuance to Portland’s reputation as the whitest city in America. Her stories made me proud to be connected to this neighborhood.

A decade later, however, I’m still having the same conversations about my grandma’s old stomping grounds. “Oh, I never go to Old Town,” lifelong Portlanders say, evoking images of a lawless, dying Chinatown full of nothing but seedy clubs and abandoned restaurants. Many envision Old Town as Portland’s skid row, a dirty, dangerous place where homelessness and drug use run rampant. But others who continue to live and work there see it as the heart and soul of historical Portland, a multicultural hub abundant with opportunity for business owners without privileged connections. When you dig deeper into the history and context of this hunk of Portland, these dueling narratives about Old Town are less mutually exclusive than they seem. In fact, they may be entirely connected.

In its heyday, Portland’s Chinatown was the second largest in the country, south of what was then Nihonmachi, or Japantown.

Old Town’s story begins when Portland does, just a few streets south of where the neighborhood stands today. In 1851, the year Portland incorporated, the first Chinatown—Old Chinatown—germinated on the inner west side. The Hop Wo Laundry and the Tong Sung Boarding House opened that same year, catering to Chinese immigrants arriving via steamer ships from San Francisco looking for work.

Over the following decades, Portland’s Chinatown grew into the second largest in the country, stretching down Second Avenue between Burnside (initially called just B Street) and Jefferson. Portlanders, Chinese and otherwise, visited the neighborhood’s groceries, pharmacies, and restaurants, dropping off clothes at the tailor and picking up fireworks from the Bow Yuen Store. At its height, three theaters produced Chinese dance performances, with grand Cantonese operas every Lunar New Year.

For more than a century, Old Town has hosted lion dances during celebrations like Lunar New Year.

As the Chinese population and presence in Portland grew, so did anti-Chinese sentiment, fueled by white workers who believed their employment prospects were under threat. Mobs regularly attacked Chinese immigrants at worksites. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, banning the immigration of Chinese laborers. The newly enacted policy only exacerbated the mounting rage and bigotry; a year later, a mob of Ku Klux Klan members raided and burned Chinese homes near Guild’s Lake in Northwest Portland. Many Chinese Americans already living here earned enough money to move out of Chinatown and buy houses on the east side around Hawthorne and Division, and without the influx of immigrants to replace them, Chinatown’s population contracted. Wealthier white investors bought up Chinese-owned businesses, those who couldn’t find work moved back to China, and Old Chinatown was whittled away. The handful of businesses that remained sought the cheaper rents across Burnside, in an incubating neighborhood starting to go by Nihonmachi, a.k.a. Japantown.

After the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act, the demand for affordable labor—often for the most dangerous and difficult jobs at canneries, timber mills, and farms—remained, ushering in a wave of Japanese immigrants in the 1890s. They had almost nowhere to go: The Portland Board of Realty’s 1919 “Code of Ethics” prohibited real estate agents and bankers from selling property or approving mortgages for people of color in white neighborhoods, and the 1923 Alien Land Law prevented those ineligible for citizenship from buying or owning land. New arrivals were left to settle in the muddy streets near Union Station, where flophouses—cheap hotels and bare-boned apartments—offered an affordable option. Scandinavian wharf workers and young Black men from the South looking for work as hotel porters and dining-car waiters also started forming a community in those Northwest streets.

Lauren Yoshiko’s family called this area home—her great-grandmother appears in the group of children below, second from left.

By 1910, Nihonmachi, where my great-grandparents lived and worked, was a bustling area concentrated between Second and Sixth Avenues, lined with Japanese-owned shops—like H. Naito & Co., the start of Bill and Sam Naito’s father’s eventual empire—as well as restaurants, hotels, and services including a dentist and midwife. The Black-owned Golden West Hotel on Broadway created the first social hub for that community, and more Black-owned businesses opened up nearby, including a haberdashery, cafés, cigar stores, and a confectionery. German Jewish and Greek merchants set up shop in this neighborhood as well, like Maletis Bros. Grocery, where my grandma would stop for an after-school snack.

“Being near the train station, near the wharf—it was a kind of natural jumping-off point for new immigrants,” says Jacqueline Peterson-Loomis, professor emeritus of history at Washington State University and executive director of the Portland Chinatown Museum. “A really interesting succession of communities of color were able to get established through the same neighborhood.”

When the US government forced Japanese Americans into incarceration camps like the Portland Assembly Center, Nihonmachi all but evaporated.

Then, on December 7, 1941, the Imperial Japanese Army attacked Pearl Harbor. Soon after, Executive Order 9066 authorized the imprisonment in American concentration camps of all persons of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast, including citizens born in the US. Japanese Portlanders were given three weeks to liquidate their possessions and report to “assembly centers” with only what they could carry. They had no idea of when (or if) they’d return home. Generational businesses, family heirlooms, recently purchased cars, and homes sold for pennies on the dollar. FBI agents ransacked homes and surreptitiously rounded up community leaders to send to more isolated, high-security prison camps further away. Military propaganda dumped gasoline on the already raging hate toward anyone Japanese. Nihonmachi disappeared almost overnight, along with everything the Japanese American community had built for 50 years.

After the war, a few Japanese business owners returned, but there was never the same community hub for them in this neighborhood. My grandmother and her parents eventually made it back to Portland in 1948, and moved into her great-grandmother’s hotel in what had been Nihonmachi. As the area’s population began to shift—the Black community hub had also relocated, to North Williams Avenue—so did its identity. The Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1943, and New Chinatown continued to grow, now in these hollowed-out blocks north of Burnside, between NW Third and Fifth Avenues.

Throughout the evolution of Nihonmachi/Chinatown/Old Town, one community remained constant: transient day laborers. In the same ways these streets supported immigrants arriving with few to no resources, Nihonmachi served as a landing pad for traveling workers without a home base, thanks to its proximity to the train station, availability of cheap places to stay, and absence of racial or economic rental requirements. In the early 1900s, buses would line up on Burnside before dawn to pick up day laborers, taking them to sprawling Salem-area hop farms. While upscale hotels existed in the neighborhood, so too did flophouses with little more than chicken wire separating “rooms.” Beyond groceries and imported goods, illicit gambling, sex work, and opium were also significant parts of the Chinatown economy through the 1940s.

Since the 1950s, Blanchet House has served free meals to transient day laborers and unhoused Portlanders in Old Town.

As more established laborers found permanent housing elsewhere and the automation of farm and logging industries required fewer workers, transient day laborers continued living in low-cost flophouses around Chinatown—eventually on the street, once their money ran out. In 1927, a group of local churches came together to offer support to the homeless population, forming the Union Gospel Mission. In 1937, they purchased a building on NW Third. A free lunch service that would become Portland Rescue Mission started in 1949; Blanchet House followed in 1952. “Portland became known as ‘The Christmas City’ in the 1950s,” says Peterson-Loomis. “Between all the people serving the poor, you could get a meal every other hour.”

The contemporary notion that people experiencing homelessness are centered in Old Town because of the concentration of social services is actually backward—these services opened there in response to an existing need, one that expanded as housing shortages, unemployment, more addictive drugs, and a lack of mental health care snowballed in the following decades.

In the 1960s, cities everywhere made a shift to demolish affordable single-room occupancy (SRO) buildings in poor and minority neighborhoods to foster higher-end economic growth in the name of urban renewal. According to an inventory

created by the nonprofit Northwest Pilot Project, downtown Portland lost more than 2,000 rental units affordable to minimum-wage workers between 1978 and 2015. The nonprofit Central City Concern emerged in 1979 to preserve SRO buildings. That same year, the timber industry drastically shrunk, spiking unemployment rates to 25 percent in cities across Oregon.

As job opportunities and affordable housing vanished, a heroin epidemic unfurled. Religiously affiliated shelters that had previously admitted tenants with substance use disorders instated “zero-tolerance” drug policies, forcing many back onto the streets. The War on Drugs disproportionately targeted Black communities, resulting in higher incarceration rates that left many families destitute. In the 1980s and ’90s, some of the state’s largest psychiatric facilities closed after reports revealed inhumane treatment of patients; they were never replaced. Then came the 2007–2008 housing crisis and its accompanying recession. As housing and health care costs increased and safety nets evaporated, more people with serious mental illnesses ended up unhoused. The COVID-19 pandemic made matters exponentially worse, shutting down most social services for a period of time (and some for good). Overall homelessness in Portland increased dramatically between 2015 and 2023; the number of Multnomah County and City of Portland shelter beds accommodates only about half of the current population of unhoused residents. The state’s mental health care system has also further deteriorated: Mental Health America ranked Oregon worst in the country for youth mental health in 2023. Then came fentanyl. Cheap, accessible, with unprecedented overdose risk and extreme withdrawal effects, it’s a danger unlike any drug that’s ever existed, for everyone, but especially people looking to numb the stress and pain that comes with living unhoused.

The bustling restaurants along NW Fourth fed locals and workers for years. Now, only Republic Café remains open.

“When I look out over people in our café, I don’t see a homeless crisis. I see a mental illness and trauma crisis,” says Scott Kerman, executive director at Blanchet House, a nonprofit on NW Glisan that provides free meals and clothing to unhoused or housing-insecure locals. “People whose mental illness…led to housing insecurity, and then how the need to self-medicate the mental illness and dull the horrors of being homeless led to addiction. ‘Homeless first, addict second’ is a common refrain among people we serve.”

As of January 2024, Oregon—only the 27th-largest state by population—had the eighth-largest population of homeless people in the country. The 2023 Point in Time Count of those experiencing homelessness found that just under 15 percent of the total unsheltered population in Multnomah County was in downtown, Old Town, or the Pearl. When you see people spending time on the sidewalk in Old Town today, it doesn’t necessarily mean they live there. This is where many have found community over the years, so even when they’ve moved into stable housing, many return in the daytime to connect with friends and get a hot meal. Youth from all over benefit from the art classes, work experience programs, and safe space provided by P:ear at its office on NW Sixth and Flanders. People in varying states of recovery and housing instability visit the Street Roots office at NW Third and Burnside for issues of its newspaper to sell elsewhere in the city at a profit they get to keep.

It’s not unusual for a medium-to-large city to have a neighborhood where homelessness is concentrated. Old Town is unique in that it provides a range of services and support in the same neighborhood—housing, mental health support, job training, and physical health services are available here. On paper, the right pieces are in place to help get vulnerable populations back on their feet and on to their next chapter—just as this area did for immigrant populations a century ago. The problem is our current support system has fallen short in the face of nationwide inflation, housing shortages, and opiate addiction, and we can’t agree on what to do next.

Business owners, aid organizations, and public officials have struggled to negotiate the balance of adequate support systems for those in need and a safe, sanitary environment for businesses. Last summer, Lan Su Chinese Garden, the Japanese American Museum of Oregon, the Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education, and the Portland Chinatown Museum sent a letter to the mayor, officeholders, and candidates seeking roles in the county and city government, demanding more resources and follow-through addressing mounting vandalism and violence in the neighborhood. The call to action resulted in an August 2024 press conference and community action plan from then-Mayor Ted Wheeler that promised a greater presence from Portland Police Bureau’s Neighborhood Response Team, the PPB Bike Squad, and Oregon State Police, in addition to ongoing support through the Problem Solver Network, a program launched in 2022 that facilitates biweekly community meetings and finds immediate solutions to vandalism, safety, and garbage issues.

The county responded in kind. It launched a long-awaited bed tracking system for all shelters. It expanded offerings at Unity Center for Behavioral Health, providing 24/7 drop-off psychiatric emergency services and upping the number of beds. And it directed grant funding from Oregon Health Authority (OHA) toward developing a more robust behavioral health workforce. There is also an increased focus on providing a system of shelters, services, and housing initiatives to place unsheltered people living in Old Town into housing elsewhere in Multnomah County. Lan Su’s executive director, Elizabeth Nye, says that from her perspective both the city’s and county’s efforts have made meaningful improvements, while she also recognizes that “addressing the magnitude of the issues we’re experiencing will require sustained and comprehensive effort over time.”

Marisa Zapata, director of the Homelessness Research & Action Collaborative (HRAC) and an associate professor at Portland State University, describes the current state of homelessness in Portland as an “intractable situation”—particularly in Old Town, the most central neighborhood with the lowest barrier to entry. “There was this industrial area that had the only housing poorer people could afford,” Zapata says. “Businesses and city leaders didn’t want them around, so they didn’t build more of the needed affordable housing, poor people’s living conditions worsened, then people opened up services to serve the people living in bad conditions, and now you have shelters and meal service sites that other people don’t want…around.”

Zapata refers to this cycle as a self-perpetuating loop—one that’s thrown the dynamics of the area off balance. The transient population has always existed in Old Town, but never at such outsize proportions to people working in or visiting the area. “A 100 percent low-income neighborhood of people living with serious mental illness isn’t good for anybody,” says Zapata.

“There have always been homeless. There just used to be other people, too,” says Old Town business owner Latif Bezzir. Bezzir has run his Moroccan rug store on NW Fourth Avenue, Kat & Maouche, with his wife, Katen Bush, for over a decade. He believes the commercial flight out of downtown has significantly decreased foot traffic, the absence of which deters others. It’s more than office workers: Educational institutions like Oregon College of Chinese Medicine and the Portland outpost of University of Oregon closed or left the neighborhood. Retailers like Compound PDX, Upper Playground, and Floating World Comics closed or moved elsewhere in the city. Attendance at Lan Su Chinese Garden is still about 30–35 percent below prepandemic levels.

Most locals agree that Old Town is out of balance. But when it comes to potential solutions, opinions are far from unanimous. Jessie Burke, co-owner of the Society Hotel in Old Town and chair since 2020 of the Old Town Chinatown Community Association, wants to make room for more businesses and market-rate housing locally by moving social services elsewhere. “We need some of our social services to relocate,” says Burke, who ran for a seat on the Multnomah County Board of Commissioners in 2024. “We need those social service agencies using ground-floor retail space for offices to move to upper office floors and free up our ground-floor retail for activation, and we need all social service providers to do the hard work of having little to no impact on their neighbors.”

Although in agreement that the ecosystem is out of whack, Zapata points out that Old Town is a neighborhood already home to a unique mix of housing options— shelters, affordable housing, and market-rate apartments. To her, it comes down to making diverse housing options available everywhere, and coordinating care for the most vulnerable. Overnight shelters, pod villages—every option has its pros and cons, and none will fit the entire unhoused population’s needs; however, trying 10 different solutions at once and pivoting before anyone can assess impact has slowed progress.

“It’s easy to say we need more housing and services, but it takes dedicated funding and it takes creativity,” Zapata says. “If we taxed effectively and collaborated regionally, I think we could accomplish a lot more with what we have. There is a lot of wealth here. The Oregon kicker? How much housing could’ve been built with that much money?”

Republic Café has seen almost every iteration of Old Town and remains open, now hosting lowkey shows and karaoke nights as it serves late-night plates of egg foo young.

But paradoxically, considering the housing need, many buildings in Old Town are vacant—commercial spaces, specifically. The City of Portland is investing dollars to create more residential spaces, helping transform two empty buildings into market-rate apartments, and has committed more than $40 million for a new affordable housing building as part of the Broadway Corridor project. Other efforts are specifically eyeing business growth in the area. The Made in Old Town project will reactivate multiple vacant buildings, creating spaces for footwear prototype development, the manufacture of shoe materials, and broader retail, cafés, and other third spaces as amenities for the larger compound. Matthew Claudel, founder of civic design firm Field States and a key architect of the project, sees manufacturing as a logical new chapter for abandoned buildings: Many of these historic buildings were intended for manufacturing, work that can’t be done remotely. “The greenest building is the one that’s already built,” says Claudel. “I believe that adaptive building reuse with advanced manufacturing and creative production is the next horizon of American cities.” And even more projects are underway: Prosper Portland has allocated $364,000 for planning and design of the Steel Bridge Skate Park, a long-term project set for the area around the west end of the Steel Bridge.

While current residents and business owners of Old Town look forward to the much-needed foot traffic on the horizon, they’re most excited for these projects to show the rest of the city what they already know: Old Town is so much more than its challenges. Latif Bezzir isn’t going to start selling rugs elsewhere—“leaving wouldn’t help anyone”—and Ian Williams, the founder of sneaker-centric café and roaster Deadstock Coffee and Gallery, isn’t looking to move his gathering place for Chinatown businesses and the streetwear scene either. He feels inspired by the range of people who go out of their way to visit his tiny storefront to connect with familiar faces.

Amir Morgan opened his tea and clothing shop, Barnes and Morgan, in this neighborhood because of its significance to the Black community—both in the past and present. For him, being in Old Town isn’t some great hindrance to his day-to-day operations. The real challenge is battling people’s perceptions. His shop—an airy space serving thoughtfully sourced loose leaf and pastries in fine-china tea settings—sits next to a cheery snack bar, Goodies, which specializes in indie brands from all over the world and sits in the former home of the Merchant Hotel and Teikoku Mercantile, a Nihonmachi stalwart. It’s around the corner from Darcelle XV, a nationally celebrated drag cabaret, and Golden Horse, one of the city’s longest-running Chinese restaurants.

“When people tell me they avoid this neighborhood, I ask, why? Also, pull up! Let me show them where to find community down here,” says Pierre Jury, a six-year Old Town resident and the man behind Chinatown Meets, a series of pandemic-era swap meets that drew hundreds to the neighborhood. “Whatever energy you’re looking for is what you’ll find. If you’re heading out with a frantic, scared vibe, that’s how you’ll feel.”

Chess Club, an ultra-cool magazine shop and mineral water bar, is one of the more exciting new businesses to open in Old Town within the last few years.

My grandma remembers sharing the bustling streets of Old Town with her homeless neighbors as a teen in the 1950s, but she doesn’t remember anyone being scared to come down there. Louis Armstrong and Harry Belafonte were getting cocktails at the Republic Café and Ming Lounge on NW Fourth. Locals didn’t start calling it “Skid Row” until the 1970s, and it became a self-fulfilling prophecy—fostering fear and inhibiting the same range of visitors from coming back. But it was still the same neighborhood. Twentysomethings were still ending their Saturday nights over hot chow mein at Hung Far Low through 2004. Republic Café remains a late-night stop for BBQ pork fried rice (or maybe an under-the-radar party). Today, you’ll find one of the best New Year’s Eve destinations on the Hoxton rooftop, drag shows and dance clubs every weekend, and beer-fueled arcade-ing at Ground Kontrol. By day, the smell of rich leather emanates from the four-generation, family-owned Orox Leather Co., rizzed-out youth line up outside Index for limited sneaker drops, Tokyo tourists browse globally sourced magazine and water offerings at Chess Club, and Fabos Tacos slings some of the city’s best new birria. Are these the kind of experiences one would associate with a skid row?

Old Town is rough; that isn’t at question. It always has been. That’s why immigrants could settle here when racist land laws gave them few other options. That’s what made it so diverse and exciting. When you couldn’t find a place to live anywhere else, or a free meal anywhere else, or a place to start a business anywhere else, you could find it in Old Town. In a way, that’s still the case. Systemic challenges for marginalized communities continue to create issues in this neighborhood, and still we blame those communities, not the people marginalizing them. What has changed is the scale and impact of the negativity surrounding its image—negativity that’s driven away foot traffic, shuttered storefronts and institutions, and further removed Old Town from the usual city rhythms.

Community leader and businessman Bill Naito dedicated decades to revitalizing Old Town.

One person who saw beyond Old Town’s prevailing narrative was Bill Naito. While president of his family business, Norcrest China Company, he pushed to preserve his neighborhood’s history. He acquired historic buildings and maintained them. When the city planned overhead lighting typically used on highways, he fought for more aesthetically pleasing, historic lamps. The MAX initially planned to avoid this area; he fought for a neighborhood stop. He negotiated with Japanese grain importers to source cherry blossom trees for the Japanese American Historical Plaza on the waterfront, and when the Saturday Market was looking for space to start out, he offered a parking lot by their office building for free.

What might it be like, to take a page from Naito’s playbook and carve out a fresh chapter for this neighborhood today, one that honors its legacy and potential? To take in all that makes Old Town so special and so challenging, all its truths at once, and recognize this vital part of Portland’s identity? It may be one of the most Portland neighborhoods left, a place where people from different walks of life have always found solace and space for creative expression. Where diversity has flourished, despite efforts to stamp it out. Sure, there’s friction as different ideas of how this neighborhood should look and feel collide, but instead of leveling what’s left into gentrified newness, vastly different lifestyles continue to coexist. Old Town is real. That’s worth protecting. And visiting more frequently.

“We can never replace what was lost,” says my grandma, Joni Nakayama Kimoto Reeves. “But we can create a place that does what Chinatown and what Japantown did for their communities. That’s where my hope is.”

Share this content:

Post Comment