Why Is PBS Teaching Me How to Sell Things Online?

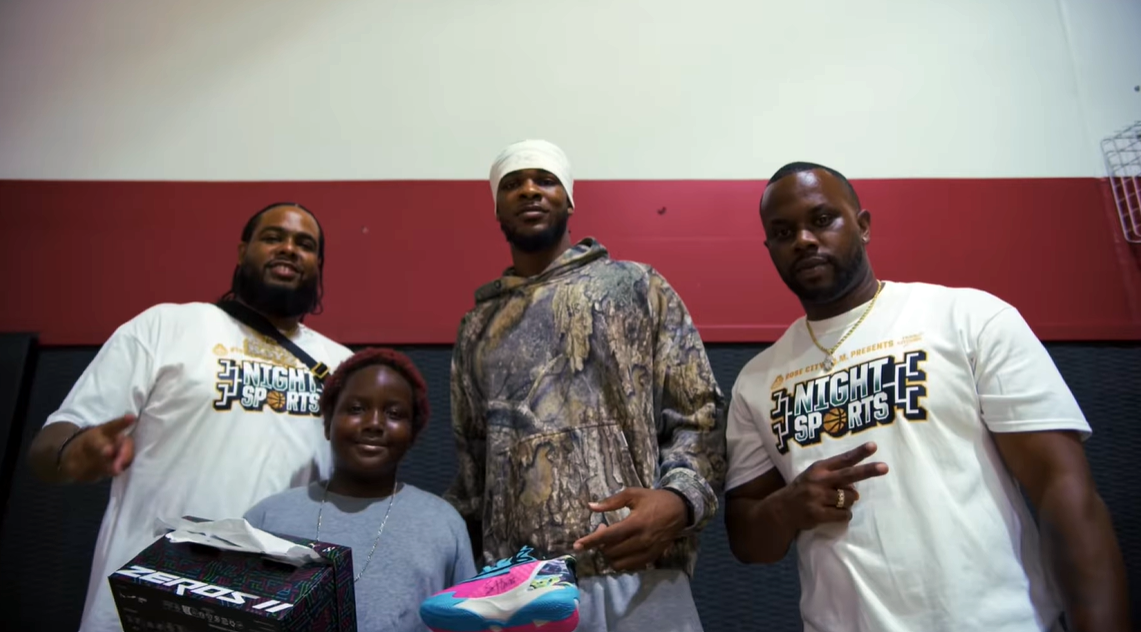

The film, which covers myriad ways of running a small business on the internet, features a Portland State University professor and several local creatives, including designer Aaron Draplin (second from left) and artist Lisa Congdon (center).

All 57 minutes of the recent PBS documentary Generation: Freedom hum with the internet’s trademark unreality. Keys audibly click text onto the screen. E-commerce entrepreneurs appear as talking heads, shot from artfully discomfiting angles and played on by public domain Tchaikovsky. A fish-eye nervily scans a computer screen as they talk SEO and affiliate marketing. “Here’s what I found for starting an online business,” the Google robot lady says, introducing a six-step plan.

You’re not supposed to like where the film puts you, but less clear is what the filmmakers have to say about that place. Before publishing with PBS, producer Michael Hall and director Christopher Sakr made the doc through their own start-up film company in Portland. They interviewed folks who’ve found their Goldilocks way of using the internet to get around working for the man, at least in theory. A good chunk of them are also local. The artist and illustrator Lisa Congdon tells her later-in-life story of stumbling into a creative career that “fed” her in a way her “regular job didn’t.” The graphic designer Aaron Draplin similarly recounts carving an autonomous career path.

This follows a nutshell summary of how the internet changed society from Portland State University media professor Lee Shaker. You’ve likely heard a version: The internet did to the twenty-first century what the printing press did to the fifteenth, times a million. The social freedoms it allowed soon bled into work, and today more and more folks are leveraging its tools to build their own microbusinesses instead of joining the ranks of a larger corporation. That traditional employment paths are dissolving, and why, is apparently a point that makes itself. “Anyone with eyes can see the state of affairs for the working person,” Sakr told me recently. In turn, Hall added, their film is “less of a critique” and “more of an acknowledgment [that] this is kind of, in some sense, part of the new normal.”

Congdon and Draplin represent common variations on modern artists’ self-employment arrangements. Opposite them is a cluster of cunning motivational speaker types who’ve cracked the code of selling products and digital media online. This class doesn’t love what they do so much as they love not having to do much. “This is all automated,” Steve Chou explains of his nuptial supplies webstore, pausing as if mid–TED Talk. “We don’t have to do a single thing.” Chou wrote a book called The Family-First Entrepreneur and runs the website mywifequitherjob.com, which, among other things, teaches you how to sell stuff on Amazon. His ideas aren’t about a dearth of careers in the marketplace; they’re about disowning that model by automating its parts via digital technologies. It’s unclear who’s making, packaging, or transporting the custom linens Chou sells, but it ain’t him.

Director Christopher Sakr (left) and producer Michael Hall.

There’s also Chris Ducker, a business coach who, per his Instagram bio, helps “midlife expert entrepreneurs grow their income and impact.” Hear it with the zeal of an ideas salesman. “As the head honcho,” Drucker tells the camera, his Cambridge accent holding the last O, “should I actually be doing all this grunt work?” On to delegation, talk of “my team.” Ducker used to have “superhero syndrome,” but no more. Soon the Google lady defines “passive income,” which another talking head quickly describes as “obliterating that link between time and money.” Sold?

Between the artists and LinkedIn avatars are the most relatable folks: people who’ve autonomous jobs for themselves that are still very much jobs, if a little freer. One guy sells life insurance freelance; he’s interviewed in a schoolyard. Another interviewee blogs on mommytravels.net. Anna Louise Harris, once a school counselor, now sells rugs on Etsy. “If you have a passion and you are really dedicated to that passion,” Harris says at one point, summarizing the American Dream circa 2025, “you can create your own job and live a life that some people view as a dream life.”

Despite the film’s breadth of subjects, Sakr says the same “inherent tools” apply across the board. Their stories collage into a manual for, as the PBS bio explains, building “meaningful businesses by turning passion into work.” We hear of the Pomodoro technique’s timed intervals; of Pareto’s 80-20 theory of effort versus productivity, i.e., working smarter not harder. Someone sprints through the acronym PLAN, but I don’t remember what the letters stand for. Like podcasts, TikToks, and magazine articles, documentaries are better at telling you about something than teaching you how to do it.

Absent from the film are Hall and Sakr’s own stories. How they met in middle school, dreamed of making historical dramas together, and started their first LLC sophomore year of high school. How Hall works on commercial photo shoots today and Sakr makes industrial training videos. How their production studio itself fits the model their movie is selling. Their bias is present, but without knowing its source, we’re left with a sales pitch flickering between dystopia and utopia. Underneath, however, are the seeds of an affecting documentary about the personal consequences of the collapse of the American workplace, and the fraught ways we perpetuate the systems that caused its collapse while trying to stay afloat.

Share this content:

Post Comment